I first applied to the AANM residency program in 2023 thinking I needed space to make my art. As the primary caretaker of my then one-year-old son, my ability to create was limited to naptime sessions (if he slept at all) or the weekly four-hour babysitter we splurged on. Drained from the relentlessness of new motherhood, I dreamt of a time where I could make art uninterrupted during daylight hours. I had no idea that this residency would be so crucial to my mental health—that the person I was before the month of May 2024 would be so wholly different from the person I became during my time in Dearborn.

As the months drew closer to my time in Michigan, I grew increasingly anxious about leaving my family behind to fend for themselves. I’m the primary caretaker of our toddler, implementing routine and structure in our daily life. My husband is legally blind, and his disability makes it difficult to get around Los Angeles, especially without a driver’s license. Not to mention his extremely demanding job in broadcast, which has unpredictable hours and makes his ability to solo parent an unreliable solution. Without me, how would my family survive??

Thankfully, my mother-in-law was able to move in with my family while I was away, providing the support my husband and son needed and easing much of my anxiety. So, I took the redeye from LAX to Detroit and landed in my new home early in the morning on a Friday. Reaching the furnished studio apartment the museum provided, I finally felt the cumulative months of exhaustion that piled up since my son was born.

Being someone’s everything, especially for a tiny human baby, is an impossible reality that every parent faces. And being that little someone’s main caretaker—making sure they are healthy and want for nothing, being their main source of life—is insurmountable.

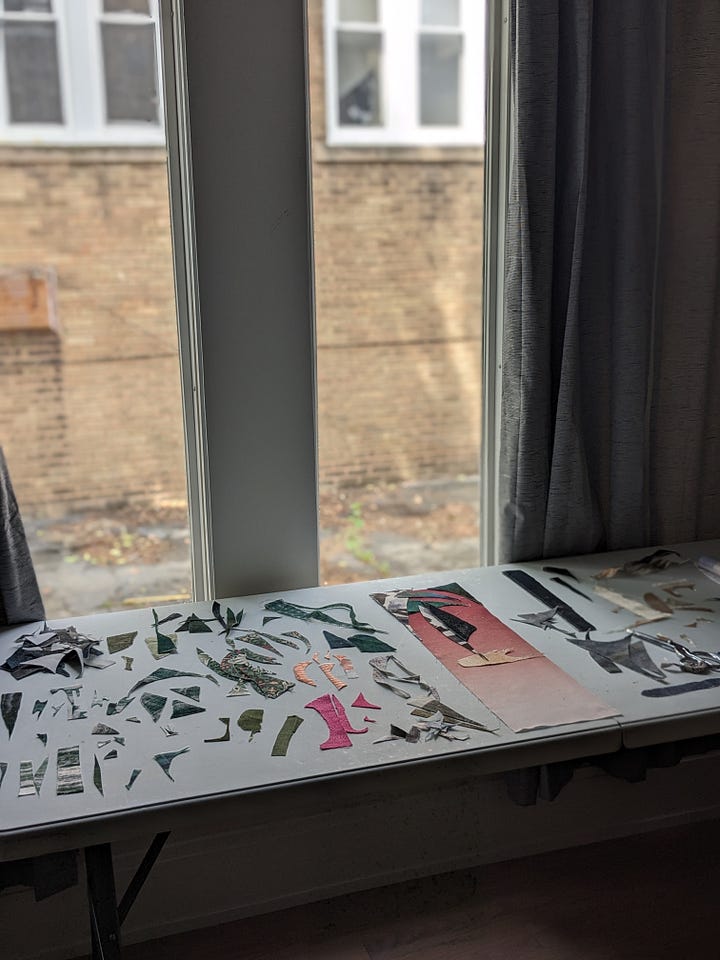

I had brought a series I was working on that addresses parenthood and the legacies we pass along; abstract tapestries that depict childhood stories I want to share with my son (pictured above, Bedtime Stories for Yuri). Thankfully, this work rolls up and fits nicely into a suitcase, an easy travel companion when my studio for the month is halfway across the country. I also brought a small altered book I began last year, my “sketchbook” of abstract paper collage and drawings. This became my visual journal for my trip, and I worked on several pages every few days, using ephemera from my outings in Dearborn and Detroit and a small road trip to Lansing. I also started writing daily morning pages, chronicling my solo adventure away from home.

It had been years since I’d lived alone, and I delighted in the ability to eat a cookie for dinner or work on my sketchbook at midnight, not needing to cook for anyone or wake up early to meet someone else’s needs. My creativity was able to flow freely, not limited to preschool hours or naptimes or my husband’s schedule. For the first time in years, I could binge-watch trashy TV or listen to the new Taylor Swift album while endlessly stitching and drinking coffee after noon.

And what a delight, to explore a new place and lose myself while walking around a new city. My father always tells me walking is the best way to learn about your surroundings, so I walked reasonable distances and took the bus elsewhere, trying different restaurants and coffee shops.

It was a respite from reality, from my own daily grind and the world at large. As a mother, I try to hide my fear and desperation from my son, shielding him so he can enjoy childhood innocence and stay oblivious to the atrocities pouring out of Gaza, out of Palestine; a place my grandparents were forced from, like so many others. Every time I look at my son, at my own family, I am overcome by the emotional duality so intrinsic to diaspora: immense gratitude for our circumstances while simultaneously grieving ongoing devastation.

But while living in this fantasyland, Dearborn, I felt safe in my environment for the first time. So much was familiar: the architecture, climate, and food reminded me of Kansas City, where I grew up, the English-Arabic signage and halal restaurants similar to pockets of L.A., where I now live. And so much was new—I was invited to one of Dearborn’s public high schools for culture day, celebrating their diverse student body. Seeing so many kids dressed in thobes and keffiyehs, dancing dabke, truly embodying and embracing their family’s culture in the Midwest brought me to tears. It healed the small, hidden part of me that had felt pressured to suppress my Arab ancestry as a child living in a red state, post-9/11.

Upon coming home, I can feel a difference in my mood and overall wellbeing; I am calmer and more present, more patient with myself and others. Even my husband and son changed, more resilient in their independence instead of relying on me to provide daily structure. I did not realize how much I needed this residency, this time away from reality, but I also did not realize how much my family needed it, too. Having this month to myself was an immeasurable gift, helping me to become a better person, mother, and artist. I can only hope that others will continue to benefit from this truly special experience.