welcoming the fall in Dearborn with Leila and the Oud

It has been a long time since I’ve lived anywhere other than Montreal for any longer than two weeks. I’ve been in Dearborn for over three weeks and the weather keeps changing. I’ve beat my record and it’s felt as mercurial as the weather. Up and down, warm and chilly. I’ve mostly experienced sunny days while here and it’s allowed me to wake up every morning to an ongoing genocide. This sun has also allowed me to read, to write, to contemplate the slow work of writing when the quick work of activism is so desperately needed. Living in Canada is like living in the shadow of the empire, it’s little sibling. Being in America is being shouted at in the parking lot of the CVS that I’m being recorded for my own safety by some towering robo-cop that looks like the machine window cleaners use to elevate the workers higher. Safety is relative when you’re in a country that lets thousands of people drown in the southeastern states, where homes are gone, where people are rendered homeless, and Biden explains in an interview that there is no more help that can be sent to them, as troops and money are being sent to Israhell that same day. This apocolyptic dystopic gaslighting campaign has been haunting us for the past year, the past two years, and in some ways, my whole lifetime. My writing is nothing if not about this, is nothing in the face of genocide if I can’t at least name it. I send whatsapp voice messages to my family and friends in Lebanon, and they reply “Don’t worry about us. How are you habibi?” and “Ta’mouneh 3ala belkoun,” and my heart breaks with every breath of “we’ve seen this before.” And yet they haven’t, not all of them at least, not since 1982, before I was born. But somehow even those of us who weren’t alive yet feel it in our bones, the ache, the repeating cycle, the June Jordan poem I read over and over again to remember it has all happened before. You know, there is so much literature by Arab writers that reminds me that Israhell has done this before but somehow I always come back to the June Jordan poem, to the lines:

“I didn’t know and nobody told me and what

could I do or say, anyway?

Yes, I did know it was the money I earned as a poet that

paid

for the bombs and the planes and the tanks

that they used to massacre your family

But I am not an evil person

The people of my country aren't so bad

You can expect but so much

from those of us who have to pay taxes and watch

American TV

You see my point;

I’m sorry.

I really am sorry.”

And somehow this brings me to my current project. These repeated cycles. These inherited histories and feelings. One day, I’m visiting my family in Zalka and we are all exiting the car, my khalto Nina, my mama, my sister, and me. When we hear a loud clap, my sister, my mom, and I slam the doors of the car instinctively and close ourselves in, as though this meager car could save us. Nina laughs at us and says, hayateh, it’s not a bomb, and though we weren’t sure what it was, not bomb, but something loud, firework, a car backfiring, she laughed at us, her door open, her nerves hardened to this sound, this everyday boom. My mom laughs and wonders how her instincts have changed, how 18 years away means her reactions differ now. I wonder how she became more like me and my sister than like her own sister and how much that removal might hurt her. I am trying to write about these legacies in my novel-in-progress, currently titled Leila and the Oud. I wanted to start the novel light, tp try to think about inheritences that feel easier. Leila becomes obsessed with the oud one day, thinking they might have inherited this skill from their ancestors, their jido, some distant cousins, some great-great-great uncle. But inheritance is never easy and so Leila will have to come to terms with the fact that no, they are not magically able to play the oud without practise or hard work. But more importantly, what other darker, deeper seeded things have they inherited from their family, a family grown complicite after the aftermath of the Civil war, of the colonial division of Greater Syria, after the creation of Israhell. Have our people forgotten our histories to pretend in an attempt to forget, to try to move forward through the pain of the past that won’t be shed so lightly? One truth that has always struck me as important is admitting what’s actually going on. Avoidance has never led us to revolution.

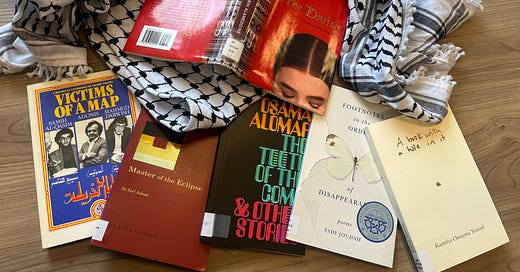

I’m reading others to help me write, and will be sharing my reading lists as the residency continues. I’m currently halfway through Rabih Alameddine I, the Divine, a novel told in first chapters. Alameddine has been guiding my writing ever since I discovered his word, ever since reading Koolaids (extremely recommend you read it) and I will continue reading his work as a guide.

Here are some others I’m perusing to see if they’ll help:

- A Billingual Anthology of Arabic Poetry, Victimes of A Map: Samih Al Qasim, Adonis, and Mahmud Darwish

- Master of the Eclipse, Etel Adnan

- The Teeth of the Comb and Other Stories, Osama Alomar

- A book with a hole in it, Kamelya Omayma Youssef

- Footnotes in the Order of Disappearance, Fady Joudah

*****